Archie Brennan in Postwar France

What follows is an excerpt from Archie’s recollections of a fascinating part of his years in France. Subsequent posts will cover the other portions of his stay there.

Come winter, I hitchhiked to Paris, and in time was asked to weave a tapestry for a fascinating man who ran what was surely the first hippie group ever. Raymond Duncan, brother of the late dancer Isadora Duncan, had formed a commune in Greece, pre-WWI. Around 1919, he purchased a very valuable piece of jewelry in Berlin, resold it in Paris at a huge profit and bought an entire old town house on Rue de Seine. It was a classic grand Parisian townhouse with a private cobbled courtyard surrounded on four sides by three floors housing all the activities of the commune: bedrooms, library, weaving studio, hand printing press, painting studio, dance studio, dining hall, kitchen, etc.

Courtyard photo taken by Hans Gallas in 2009, see http://gertrudeandalice.com/blog/2009/08/19/august-in-paris-in-the-sandal-prints-of-raymond-duncan/

The courtyard was Raymond’s stone carving area. Daily he was there, in his seventies, wielding his seven pound hammer and stone chisel. Along with the main leaders of the commune, he was always dressed in a loose, long white, handwoven linen toga, tied at his waist with a silver braided cord. His long silver hair and thick lens glasses, and his short, slight build did not conceal his physical agility, endlessly chipping away at his large sculptures.

The commune’s income was provided by a changing number of members from around the world, mostly older, wealthier women, at times accompanied by their husbands. I recall in great detail a trip to a major super market to purchase some lengths of light wood to adapt the floor loom I was to use. There were three of us. We drove across the town in a large new diesel Mercedes owned by a very slight, short Japanese-American husband of one of the commune guests. We wandered in line through the big store: Raymond leading in his toga, the Japanese man immaculately dressed in a beautifully tailored black business suit, white shirt and tie, and I, lagging behind trying to appear as if I were not part of this trio!

My agreement was to live in the commune, eat in the dining hall (a totally vegan diet!), and be paid every two weeks. On pay day I would go out alone to have a large meal of steak, cheese and a litre of milk. The communal meals were extremely simple, held in a dining hall with two long tables. The cooks were American, full time “members” of the commune. We simply stood in line and our plates were filled with a range of vegetables, cooked and/or raw, then fruit. We drank water. I cannot recall what breakfast was, but I am sure there was no coffee!

Yet there I learned much about an alternative approach to living. Everything was by hand, even the publications. First the typeface was hand cast in lead, the paper was hand made, and hand bound after printing. My first huge shock was the source of the weft yarn I would use to weave my tapestry. Although the warp was a commercial cotton yarn, when Raymond handed me the weft yarns it was a sack of clippings direct from white, brown and black sheep! First I had to hand card a range of “colors” by blending on the carders, which I then had to hand spin on a drop spindle (no spinning wheel!) before and during the weaving. This was all a totally new experience for me! I accepted this—it was the philosophy of everything that was produced in all the workshops, and it opened my mind to rethinking everything I had learned in my 24 years of living. During my time there I became too efficient at controlled hand spinning so I switched to a left handed approach to “free” my skills. I did not adopt this approach in the long term. Even after more than 50 years, this skill is still with me, and because of my experiences during this time, my creative thinking is bound by the ever present question,“I wonder what would happen if…?”

There are no photographic records of my weaving with Raymond. At that time there was no way I could afford a camera! Somewhere there must be a publication or book on Raymond Duncan.* The commune worked by offering the experience of a lifestyle for paying guests, and they had further income, I guess, by Duncan’s occasional return to tour around his original home base, giving dance threatre and lectures around San Francisco. The domestic set up in Rue deSeine was good. I had a huge personal, third floor room, and a well lit weaving studio. Raymond was more of a philosopher than an artist, but I wove from one of his paintings that he had once exhibited in the Salon de Refuse where many later successful artists, like Picasso, had exhibited when rejected from the annual French Academy show, probably around 1908-1910.

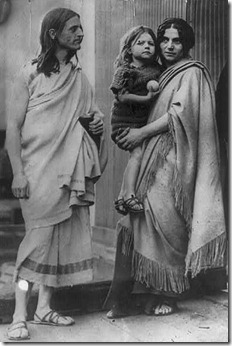

From Wikipedia, Raymond Duncan with his Greek wife, Penelope, and their son, Menalkas, c. 1912.

For further reading about Raymond Duncan:

*The Raymond Duncan Collection, which includes his correspondence, newspaper clippings about him, and various other records is housed at the University of Syracuse and is available for perusal by arrangement with the University.

Article from the “Harbor Grace Standard” in Newfoundland, Canada, with photos of Raymond Duncan, circa 1949.

“New York Times” article about Raymond Duncan’s arrival in Berlin in 1907.

Wikipedia information on Raymond Duncan.

–This is a fascinating time in Archie’s development as an artist, and if you have further information about Archie from this time period, or Raymond Duncan or this commune I’d like to hear from you!